By Andy Marlow

Lawyer and Birkbeck LLM Student

It is 4:24 p.m. on 5thMay 2018, and I sit in the ‘Royal Shit’ room at ‘Temporary Autonomous Art’.

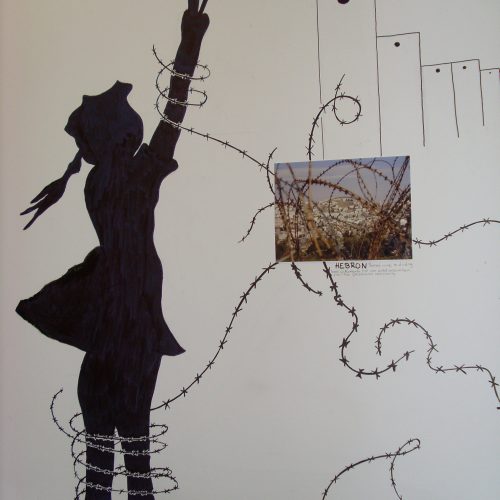

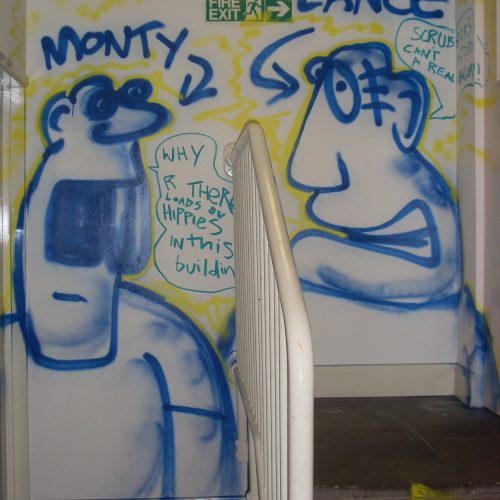

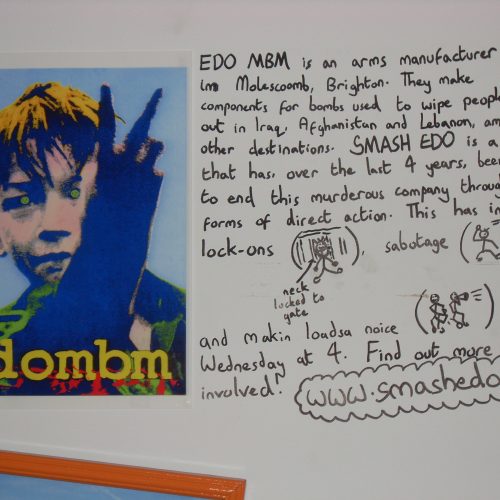

Around me are pieces of artwork that fit well the name of the group who decorated this space.

There is a poster of a ‘no smoking’ sign, edited so as to read: “No Smoking. It is against HUMANSto REIGNin these premises” The severed head of a deposed monarch is depicted where the cigarette would normally be.

There is a line drawing of the Queen’s head, with security cameras for eyes and the label ‘CCTV’ above her hair.

There is a slanted photo of the royal family, on which the slogan “STERILISE THE MONARCHY” is engraved in stencil-like font.

This is Temporary Autonomous Art (at an event of the same name), which is a form of art whose inspiration is so clearly drawn from Hakim Bey’s writings on the Temporary Autonomous Zone, or TAZ.

Bey writes in the anarchist tradition. He eschews ‘revolution’ in favour of ‘uprising’, critiquing historical revolutions as the mere replacement of one toxic State for another. Instead, he proposes the TAZ, which he describes as “an uprising which does not engage directly with the State, a guerrilla operation which liberates an area… and then dissolves itself to form elsewhere / elsewhen, beforethe State can crush it” (Bey, 2003: 99).

From comments such as these, it is no surprise that events inspired by his theories should attract anti-authoritarian artists.

The same-named ‘Temporary Autonomous Art’ is annual event organised by Random Artists, a gathering of squatters and artists who seek to take disused spaces and display their art in a different London location every year.

Tracking a chronology of Temporary Autonomous Art is alusive: where it began, how it became what it is today understandably exhorts its attendees to keep its details off social media and search engines.

A speaker is talking about various examples of ‘free’ spaces around the world. This idea of ‘free’ space is a common theme echoed by other speakers, who relate their experiences of them, whether speaking from lived examples or theoretical insights.

One woman speaks of the years she spent in the Amsterdam squat scene. Her revelations about the hidden hierarchies in spaces that on the face of it espouse equality and autonomy, are eye-opening.

Her experiences squatting in Amsterdam will mirror those of other squatters closer to home in England. Both jurisdictions have recently seen the enactment of legislation that criminalise squatting in one way or another, whether that be the Dutch Squatting and Vacancy Act 2010 or the now infamous section 144 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012.

It is thankful that English Law has so far limited itself to criminalising only residential squatting. Otherwise, those squatting in commercial and industrial buildings would face more than the present risk of possession proceedings in the County Court as a result of their actions: criminal sanctions could be at play, too. If this were the case, organising events like Temporary Autonomous Art, usually taking place as it does in squatted commercial buildings, would become a much more risky venture.

Another speaker discusses the theoretical dichotomy between hegemonic and existential freedom. Hegemonic freedom, he explains, is what capitalism currently gives us: the increasing freedom to buy an increasing array of goods and services offered to us as commodities. The existential freedom of being able to question this commodification and think together an alternative is in increasingly short supply.

If the TAZ is about an uprising of autonomy, then it is also about the decommodification of art. Bey writes: “[i]n the TAZ art as a commodity will simply become impossible; it will instead be a condition of life … TAZ is the only possible ‘time’ and ‘place’ for art to happen for the sheer pleasure of creative play” (2003: 129-30).

If Temporary Autonomous Art is an attempt to put the TAZ into practice, it certainly walks the walk it seeks to talk: for at the same time as our speaker is advocating existential freedom in place of the hegemonic variety, attendees in other rooms are enacting their existential freedom in the pens they put to paper and the brushes they put to canvas.

Such existential freedom, it appears, involves breaking rules. In just the same way that rules are being broken in the very happening of Temporary Autonomous Art, in that it is taking place in a squatted building, so must rules be broken in the production of art. Bey invokes Stirner to speak favourably of “‘breaking rules’ of ordered perception to arrive at direct experiencing” (2003: 80), in a manner analogous to the expression of ‘wild’ creative energies. One expects that the art being practised here aims at just such a breaking of rules, in order to express one’s own nomosin print.

Whereas the organisers of Temporary Autonomous Art would claim the freedom to open up this building as a space liberated from capitalism where free artistic expression can reign, the owner of this space might instead claim the freedom to prevent the organisers from getting in.

Bey, for his part, might address this conflict by speaking of enclosure. He decries what he calls “the enclosure of the map” (2003: 101), wherein “[t]he last bit of Earth unclaimed by any nation-state was eaten up in 1899” (2003: 101). Similarly, one may critique the enclosure of the commons, and hark back to a time before every bit of land was claimed by a private owner. Before this time, those seeking alternative ways of life could cross the frontier to start something new in terra incognita; now, such souls must conform to the norm, or else transgress the law of the land.

Many of those attending this event would be questing for this lost freedom. To the extent that claiming it involves risking confrontation with the authorities, as one speaker relays: “who told you freedom is easy? Freedom is hard.”

So what is the link between art and law, when it comes to Temporary Autonomous Art?

One might suggest that a ‘free’ space for artistic expression is being created in a space purportedly outside the law, where norms alternative to the prevailing capitalist system try to form their own informal order.

One might point to the contrast between presence and representation. Bey’s aim for the TAZ was to “imagine an aesthetics that… removes itself from History and even from the Market… [and that] wants to replace representation with presence” (2003: 128). A similar aim may be stated for legality. One may ask: how should law be created? By representatives voting on norms that then become binding on those whom they represent? Or by those represented themselves, doing away with their representatives and agreeing their own norms directly amongst themselves? Bey’s TAZ, and Random Artists’ Temporary Autonomous Art, would choose the latter, in its legality and its aesthetics.

There are potential variations in tone. Is it a free space, with the positive connotations that might imply? Or a ‘lawlesss’ space, as its detractors might otherwise claim?

Or is there in fact no contradiction between the two terms? The ‘Ontological Anarchy’ preached by Bey, and the individualist anarchism of Nietzsche and Stirner by which he is inspired, finds the most intense form of freedom in the praxis of lawlessness – or, rather, in the act of transgressing law. Unlike other anarchist thinkers, Bey does not envisage a utopian future free from the shackles of the State and its laws – on the contrary, he relishes their existence, and takes pleasure in their violation. He writes of his desire “to accept the rules in order to break them and thus attain the spiritual lift or energy-rush of danger and adventure, the private epiphany of overcoming all interior police while tricking all outward authority” (2003: 87-88).

Perhaps, in the end, this is why Temporary Autonomous Art, or any attempt at a TAZ, must indeed be temporary: it lacks the revolutionary belief and imagination to propose a long-lasting alternative to the present social arrangement, accepts as inevitable the return of the State-based legal order after however long the TAZ happens to hold, and exists simply to enjoy the intensity of what is experienced during that time when the inhabitants of the TAZ, whether it be Temporary Autonomous Art in London or the Zone A Défendre in France’s Notre-Dames-des-Landes or the NoTav community in Italy, happen to be in occupation.

As I leave, the impending return of the State into this purported time and space of autonomy is made clear to me. Earlier in the day, some people who had visited Temporary Autonomous Art had allegedly decided to take the art outside. Locals became annoyed, making complaints about graffiti, and police were called. Twice during my time there, I saw police standing outside the gates; and as I leave and approach my bus stop, I see a police van waiting not far from the venue. I cannot help but think they might be preparing for a raid, should they be ordered to enact one.

As I reflect on this unfortunate final impression of my time at Temporary Autonomous Art, I am reminded of one final quote from Bey’s works, as a leave the building and the reclaimed space, for however brief a temporality (2003: 91): “[t]he image of the inspector or detective measures the image of “our” lack of autonomous substance, our transparency before the gaze of authority. Our perversity, our helplessness.”

Hakim Bey (2003), T.A.Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, (Autonomedia: New York)

Temporary Autonomous Art should return in 2019. Details are expected to be made available nearer the time by Random Artists.

Andy Marlow, Lawyer and Birkbeck LLM Student, email andrew.jonathan.marlow@gmail.com.