Interview by Swastee Ranjan

Interview by Swastee Ranjan

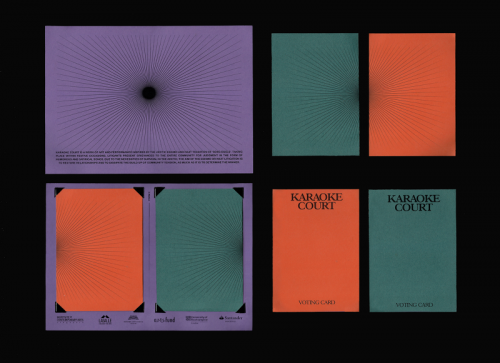

Imagine a court in which litigants sing their case and solve their dispute through song duels in the presence of a jury audience who decide the winner – Karaoke Court, an art performance led by Artist Jack Tan is precisely this but it would be a misnomer to think that it is only this. I first came across Karaoke Court through my own readings in law and aesthetics and was absolutely intrigued with the many intersections between art and law. So powerful was the first impression, that when I wanted to conduct an interview for the Art and Law Network, I decided to sit down with Jack Tan himself and understand his creative inspiration and intellectual motivation. Following is an excerpt from our very invigorating conversation.

Thank You Jack, for interviewing with us – we, at the A&L network, have been great admirers of your work, and wanted to sit down with you and talk about your work and your inspiration. So, since I am very fond of Karaoke Court and see within its performance a nuanced interaction between art and law, I want to start this conversation with your description of Karaoke Court and what was the process that led you here?

Jack Tan : Karaoke Court is an art and arbitration process in which litigants come together to resolve their disputes before a jury-audience under binding contract via karaoke singing. The inspiration for Karaoke Court came from my first year jurisprudence course on the LLB. I remember being fascinated by Inuit approaches to dispute resolution during a legal anthropology lecture, particularly the method of ‘Song Duel’ that involved community-based performance and singing as litigation. That was 25 years ago and it was only in the last few years that I thought any of my legal education or experience was in any way relevant to artistic practice.

After graduating law school, I did an MA, then stint of paralegaling, clerking, human rights case-working and then finally doing a training contract at a commercial law firm. I then left to train as an artist. At the time of leaving in 2004, I thought that I had turned my back on the law forever. But a few years ago, it occurred to me that law was a pretty interesting topic for an artist. As I moved further and further away from my time in law, I began more and more to see the law as a cultural object (a ‘humanities’) and also a potential art medium. And so in 2014, I decided to try and make a work that used law as art. This is how Karaoke Court came to be.

When I read about Inuit methods of dispute resolution as an undergraduate, it struck me that the form of a society’s law, and indeed its litigation, is produced from that particular society’s worldview and needs. For example, we in the Commonwealth find it useful to be adversarial, to attribute blame and to speak formally in court as compared to what happens in a Song Duel which is to be conciliatory, to use humour and to sing as litigation. The Song Duel’s main aim is to act as a release of pent up tension and to mend the community fractures caused by the dispute between individuals. Not so much about casting blame. This is perfect for a society that exists in the harsh Arctic environment and requires a high level of cooperation for survival. However, I thought it was quite extraordinary that performance, humour and music as legal method resolves disputes in a way that is not just about establishing facts or ‘truth’ but that it also mends interpersonal relations and the social fabric. So, inspired by this, I devised a way of doing this with the legal instruments available to our society today, i.e. the arbitration agreement.

Is it fair to say, then, that you brought law to the arts? And were you conscious of the interaction between law and art?

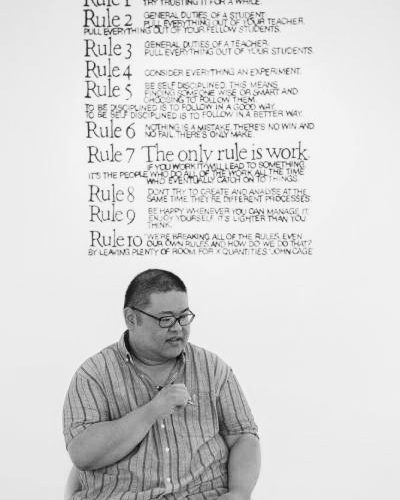

Bless you for suggesting that but it is not quite fair to say that! People like Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Carey Young, Marco Godoy have made work in this area, and you could even trace a history back to the Artist Placement Group’s contract negotiations and of course Augusto Boal’s ‘Legislative Theatre’. And I even know of a musical produced a few years ago of John Rawl’s ‘A Theory of Justice’! But all my past work—sculptures, performances, installations—have been informed by a fascination with the rules that underpin behaviours, images, spaces and objects in society. So I have always been interested in a wider sense of the law. But it wasn’t until recently that I became interested in thinking law alongside art and as such, the law’s technical possibilities for producing art. And in the case we are talking about—Karaoke Court—of using arbitration procedures or arbitration law as art.

I also ways read around my artworks. So producing ‘legal artworks’ also allows different philosophical silos (jurisprudence and aesthetic theory) to come together for me. Looking at my bookshelf at home my collection of art books have grown alongside my old law books over time. And it prompts me to ask how does someone like John Rawls talk to Jean-Luc Nancy, or how does (John) Finnis speak to Duchamp, or Ronald Dworkin to Karen Barad? I wonder how these different philosophical worlds are colliding and ‘intra-acting’ to use a Baradian term, and how could they collide materially and affectively in the work of art.

You mentioned that you have done ceramics, what about ceramics attracted you to pursue it as a field of inquiry?

I have always been interested in pottery. Not far from the law firm where I did my training, there was an art centre offering ceramics classes. So, that’s where I went once a week while working at the law firm. In my first pottery lesson I was taught how to make a pinch pot by taking a tennis ball sized lump of clay and sinking my thumb right through the middle of it. The feel of the wet weight of clay, how it resisted and gave way under pressure, the human imprint – I was hooked within the 30 seconds it took to for me to sink my thumb into the material and open it out into a rudimentary vessel. From there, one thing led to another and I decided I would leave my job and go and do a ceramics degree at Harrow Ceramics (Westminster University).

I am fascinated with this, because a ceramics degree is not something, you hear of often.

Yes, it’s a craft training and sadly so many ceramics degrees have closed down in spite of the huge need and surge of interest for material encounter in recent years. For me, it was the most wonderful coincidence to choose a craft training because it’s so similar to law. I trained as a commercial litigator. And written text of course was the main medium that we used all the time (talking on the phone came a close second). Ten times a day I was referring to, pondering, applying, stretching, digging in that book of words called the Civil Procedure Rules. It was interesting then to go in to another process-related mode of working – ceramics. They both had synergies. There’s something irresistible and captivating about ‘process’ itself: about producing something in the world that follows a procedure. But learning also that procedure isn’t just something that has to be followed without creativity; written procedure is like clay which you can apply, stretch and move to an optimum extent, but also realising that there are some points where you can’t really move it any more without breaking it. I think of a rule like a vessel – it is a container for meaning, but the way that meaning can sit inside the rule or around the procedure, or the way the meaning can ornament, and thus frame procedure is very much a creative process. While much of my current practice is in performance now, what I learnt about procedures and process comes from law and ceramics.

Yes, one can see that in Karaoke court.

Karaoke Court is a good example. Most people look at arbitration law and might say: “I have to do arbitration or mediation in the way it is conventionally done”. So, we all wear proper shoes and dark business suits, and we go to a conference room where we have an arbitrator who sits at the head of the conference table, and we all will sit on opposite sides. And the arbitrator will go through the process of hearing from each side and essentially enact a mini court. I decided to approach the arbitration rules as if they were like any medium that would be in my studio: plaster or wood for example. There are some limitations on what can be done with the material, but also many possibilities. As a ceramicist, I know that clay doesn’t always have to be a round pot. It can be anything within its own physical limitations—square, blobby, figurative— and the final object can also be placed somewhere unexpected thus creating different contextual meanings. Like any other art material, one could turn arbitration into what one wanted so long as the parties agree and that all the legal requirements of an arbitration were met. So, that’s what I did with Karaoke Court and as such, through this work, we can understand arbitration in a completely different light.

What appears in your work is some sense of dynamism – between the worlds of art and law. But what about the question of representation – how art represents law doesn’t seem to have much space in your work?

Yes. Because I am not interested in depicting or illustrating the law in the same sense that I am not someone who likes or is good at painting landscapes or portraits in order to accurately recreate likenesses of places and people. The fact that law is represented in a lot of my work comes from the fact that I am using law as medium rather than a particular aim to represent or laws or legal issues. There are many lawyers and campaigners who are way better at doing that than me!

I am also ambivalent about using art as a way to change the law. I don’t think the relationship between art and law is that direct. Law has an aesthetic dimension which we can access to create work in order to make visible that very aesthetic dimension. That aesthetic dimension is not uninfluential. But its influence isn’t cause and effect. It has to be detected in other ways and using other yardsticks. As such I couldn’t improve or ‘fix’ the law with art even if I wanted to because ‘fixing’ is a cause and effect thing. Also the moment I instrumentalise art to explicitly create social good, it stops being an interesting open-ended enquiry for me.

Yes. And even though you do not instrumentalise art – you do have an understanding of aesthetics with regards to law – you break apart law, and take the form of the law to be more than what it just is. I can see in your work, the notion that the text of the law is not merely the law. There is something else that describes the law. So, in my understanding, your work highlights that aesthetics is not merely how the law is conducted but also escapes the given law.

I’d agree with that because my conception of the law is very much beyond the text. For example I sometimes imagine a particular society that may have no written code, no text. But it still has formal law through which resources are distributed and order is maintained. So for me law pre-exists or exists beyond the text in that sense. The fact that our society chooses to use written text to process and contain the law means that our law is bound up in and defined by specific operations of semiotics and grammar. And that has led to a specific timbre of law in our culture. But that was our choice.

The law, like Art, is something that human beings do. It is deep in our nature. To me, law is an instinctual perception of differences in power, resources, presences and then a deciding of how these are to be allocated and distributed and behaved around. For example, If you and I met face-to-face somewhere, there’s already a kind of law in place between us because we may be aware of our different physical sizes that would denote different claims or access to strength or space or prominence. We may then agree implicit or explicit rules about what do with this relation between us and how to express this formally. This is law to me, and also sculpture!

In your work, you put special emphasis on materiality whether in terms of performances or in terms of a certain semiotic reference – such as for the Karaoke Court, you use flyers and logos. Do you want to say something about that?

Law has always used visual and material culture to reinforce what it is. You only have to walk around the Royal Courts of Justice in London to realise that, or any supreme court in any country I bet. But let’s say we meet in a new land somewhere and agree that this patch of land is mine and that patch of land is yours. But for some reason we are not happy with just a verbal agreement, and feel we have to draw a line between us. That line could be drawn in the dirt or marked out with stones, but it often takes the form of a fence or wall. That line is where a visualisation and materialisation of law begins. Depending on how much we like and trust each other we may decide to build a high iron fence or a short hedge. At some point we may want to declare this to third parties by materialising more marks called road signs or ‘boundary stones’ as the ancient Babylonians did. These are aesthetic decisions we are making to embody the law. I think law and aesthetics in this way have always been close – and there’s always a conversation between the two. That is why it has been important for me to be aware of material and visual symbolism within my work through use of contemporary signifiers such as logos, branding and graphic design, and to always re-understand how law is creating a visual and material culture and vice versa.

Yes. I am interested in knowing what inspires your creativity the most.

It’s really weird that I can’t answer that question and it’s because I don’t see myself as some kind of nineteenth century artistic genius who sits in a studio or takes a walk through a landscape and suddenly gets inspired by a host of golden daffodils. It’s just work for me – it is a process of mining. I go from one thing to another. So it’s much less ‘inspired’ in the grand sense and more like “I have some crossover here” or “What’s that thing over there? – I’ll go and have a look at it” or “You’re interesting, let’s work together on something”. Oh I know! It is not inspiration – an artist’s engine is curiosity, and that’s what keeps you going. That’s what takes me to different works.

What are you currently working on?

I am currently working on my animal courts project for next year inspired by the animal trials that happened in medieval Europe. Animals in those days were prosecuted either in ecclesiastical or secular courts for the crimes they committed against humans or human property: sometimes murder and often damage to crops. Next year, I have been commissioned by Compass Festival in Leeds to do a day of live animal hearings. We are going to … at least the plan is to … take over Leeds Town Hall to set up a ‘Department of Animal Justice, a division of the UK subordinate courts, and have proper signage and everything as if we were one of the public sector tenants in the Town Hall. We will hold a day’s trial of various animal cases. Local animal charities and petting zoos will nominate their naughty animals for trial. I will also work with Leeds barristers who are going to prosecute and defend these animals. I think the work will bring up interesting questions circulating at the moment around legal personhood and posthumanism.

Which artists do you admire? And which philosophers do you think have influenced you in your work?

Theaster Gates is a very interesting artist, not least because he is a potter! Based in Chicago, his works are to do with planning and regeneration, and he thinks of city as medium. He has transformed large parts of Chicago and has done a lot to regenerate whole neighbourhoods as works of art: you could perhaps think of this as ‘city planning as art practice’.

I admire the work of the ‘Artist Placement Group’ (APG). They were working in the UK throughout the 60s and even into the 90s and their aim was to place artists within industry. They would, for example, negotiate with organisations such as the British Steel Corporation and place artists within such organisations giving the artists access and insight into corporate culture. These artists became an intervention or an insertion into a world that operated from an entirely different perspective. In effect, it inserts an aesthetic practitioner into a rationalist capitalist paradigm. It is very ‘Puck-like’. The APG generated disruptions and these disruptions helped produce art as well – so, often in their exhibitions they’d display correspondences between the artists and the management showing how much the two worlds were at cross purposes.

In fact, last year I did a ‘placement’ as the first ever artist-in-residence at the Singapore Courts with their Community Justice Centre. Although I am very comfortable in a court environment having done more than my fair share of outdoor clerking, the important thing is that once you are in there as an artist, do not slip into thinking like a lawyer or legal worker. You have to hold on as much as you can to being the artist because that is our expertise and where we can give most value. The interventions don’t work otherwise.

In terms of philosophers, I have already mentioned Rawls and the social contract philosophers whose legal imagination encourage me a lot. I also really enjoy not understanding Hegel and return to that bewilderment regularly. Also lately I have been delving into Karen Barad’s work because, in our information and quantum age, I believe that we have to stop thinking of knowledge as a Newtonian object. Further I think that we have to go beyond postmodernism now and as such have been reading Gillian Rose who tantalises me with how a return to the jurisprudential as the basis for knowledge might achieve this beyond. Stefano Harney and Fred Moten are also important guides, who among many topics, write about how we can navigate the logistical world and the critical itself through a Black studies approach.

So finally, there’s something to be said for art for art’s sake?

Definitely art for art’s sake. Art or more specifically the field of aesthetics is not subservient to ethics or logic. I think aesthetics is an entirely separate paradigm from ethics and logic: so whether something is ‘beautiful’ or not is different to whether something is good or bad, or empirically true or false. And by ‘beautiful’ here, I don’t mean ‘pleasurable’ because a lot of great art is uncomfortable, horrific or abject. I am interested in making art for its own sake but I very much hope that my art resonates with my politics; it often does but sometimes it really surprises me.

Thank You Jack, that was a wonderful conversation that gave us plenty to think about concerning law and art and the role that aesthetics plays in carving them out of their neat boundaries.