by Sean Mulcahy

From 6-8 September we ran an Art/Law Stream at the Critical Legal Conference. We were very lucky to have the artist and lawyer Jane Hinde come and share her work in installation from, as well as an inspiring talk on her work as a practitioner in both the law and art.

Below is a wonderful response from Sean Mulcahy, to the experience of Jane’s art and law, at the CLC.

Jane Hinde’s As They Fell is a deeply personal work. As audience to the installation, there is a sense of being privy to personal conversation. Eavesdropping and overhearing is, after all, the prime mode of engagement with the work. Through putting on earphones, the audience gains access to tape-recorded conversations between police and interviewees. The earphones envelop the listener in these interviews. The earphones operate to put the audience in their own world. They enclose the space around the listener’s ears, creating an acoustic chamber or what Salome Voegelin terms a “listening space” (2010: 101), a space for concentration and attunement. In this space, the audience can hear various sounds beyond the vocal. There is the ever-present background noise of the recording. The bleep of the recording ticking over provides a rhythm to the piece.

There is also uneasiness to this listening due to the issue of consent. This discomfort stems from the question of whether the audience is allowed to listen. From this discomfort stems a further question: how does the artist – the curator of this listening – select what to play and how to frame the work? This is particularly relevant because of the verbatim nature of the work, and is a question that verbatim theatre practitioners regularly face (Hammond & Stewart 2008). Hinde was working from five hours of recorded interrogation, which was edited into a five-minute loop. This raises in the audience the question of what is not included. These absences invite the audience to construct their own narrative of the unsaid. The short loop of the artwork only provides narrow passages into the greater interviews. The law is transmitted through a thin tape, which offers only a small glimpse into a tunnel. The audience must tunnel into the interview through this passage offered.

Time is a crucial dimension of the work. Five hours of police interrogation versus a five-minute recorded loop is a very big discrepancy. The interview is an oppressive form of durational performance; for the audience to the artwork, the recorded loop is like a short treat or a tidbit. Questions of place and space are also very much present in the work. The work is focused on the confined room of confessional spaces where police interviews take place but is simultaneously situated in the public space of the gallery. To accommodate audience interaction, there is flexibility to the furniture (e.g. the chair can be pulled out to be sat upon) and thus a flexibility of movement in the installation space. By contrast, in the interrogation room, there is a fixation of furniture (e.g. the interviewees chair is commonly bolted down to the floor) and thus a fixation of movement in the space. The fixation of furniture is a mechanism of controlling the interviewee. The parallels between the interrogation room of a police station and the confessional of a church are clear. The act of sitting is crucial to both performances. There is coziness to the structuring of space with the interviewer and interviewee in close proximity. There are also scriptural resonances between a police interview and a religious confession in that in both the speaker is presenting themselves to themselves in their own words. Time collapses in the interview room, but space is confined.

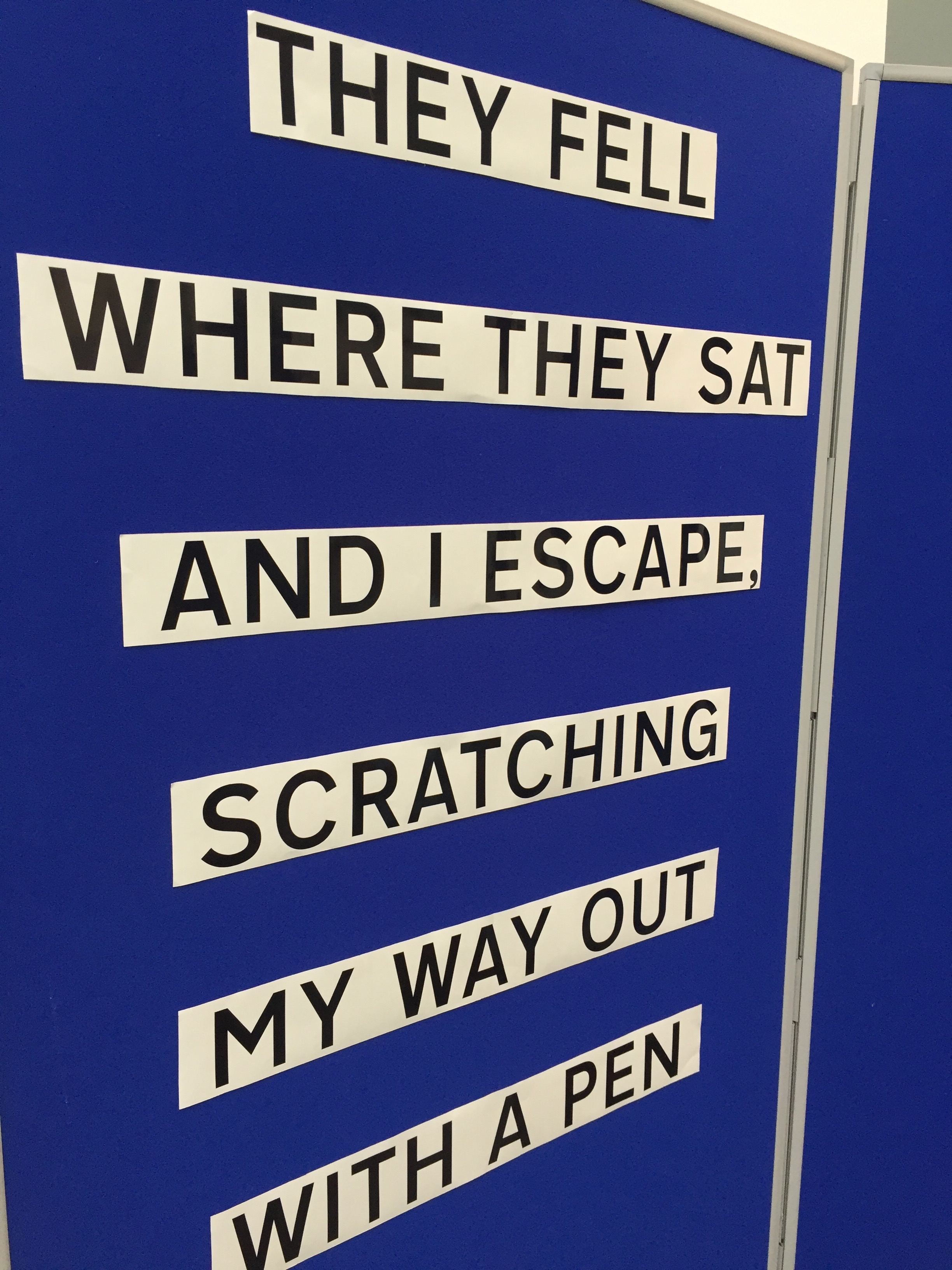

Interview tapes form part of the archive of a criminal investigation. They have an afterlife beyond the investigation (Biber 2018). As much as an acoustic presence in the work, they are also visually present in their physical form, moving as they play. The presence of the tapes contrasts the absent body. There is a lack of bodily presence in the work; the actors are only present in voice. The work is fundamentally concerned with giving voice but lacking body. The tapes thus act as a remnant of the body. There is a relation between the tapes and the images that accompany the installation. In both, there is a sense of the interviewee being trapped and trying to emerge.

What the tapes expose is troubling. However, I was left questioning: what does the artwork invite us to do? What is the work of art/law? As provocative art should, Hinde’s piece leaves its audience with questions not answers. Discovering these answers – and I use the plural deliberately as there can be a plurality of responses – is part of the ongoing project of art/law and what this very network is striving to achieve.

Katherine Biber, In Crime’s Archive: The Cultural Afterlife of Evidence (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018)

Will Hammond & Dan Steward (ed), Verbatim Verbatim: Contemporary Documentary Theatre (London: Oberon, 2008)

Salome Voegelin, Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art (New York: Continuum, 2010)

Sean Mulcahy is a Law and Theatre PhD student Monash University and the University of Warwick, and actor.