Integrative Arts psychotherapist Jo Parker speaks of her involvement in Brighton Oasis Project (BOP)’s ‘Art of Attachment’ project, and how art can transcend and transform in the name of justice.

‘The authentic voice may not be the one you want to hear. All true art is subversive at some level or other, but it doesn’t simply subvert literary clichés and social conventions; it also subverts the clichés and conventions you yourself would like to believe in. Like dreams, it talks for parts of yourself you are not fully aware of and may not much like’. The Writer’s Voice, Al Alvarez (2013)

I have been working for ten years as an integrative arts psychotherapist at Young Oasis, a service of BOP, specifically for young people and children with substance misuse in the family. Working with creative processes is integral to BOP in its unique provision of drug and alcohol treatment to women and services for children and young people affected by histories of substance dependence.

Inside the therapy room I work using the arts as a way to access the unconscious. I use words and metaphor. There is also a sandtray with objects, clay, paint, felt tips, musical instruments, puppets, dressing up clothes. I might invite a client to ‘show me’ what they are feeling by making an image. This process can be a powerful way to externalise internal processes and work on them. As a team, over the years, we have delivered Outdoor Art groups, exhibited in local galleries, worked alongside local artists and collaborated with organisations such as South East Dance, Fabrica and Brighton and Sussex universities.

The Art of Attachment project was one of our flagship projects and was conceived as a way of researching and exploring individual experiences of attachment. Attachment theory, originally put forward by John Bowlby in 1969 and developed with collaborator Mary Ainsworth, remains a dominant theory in the field of scientific research today. It examines the human need for connection and relationship, with particular focus on the parent-infant bond. Funded by the Wellcome Trust and Arts Council England, the Art of Attachment project was comprised of a programme of workshops, exhibitions and seminars that took place over eighteen months 2017-18.

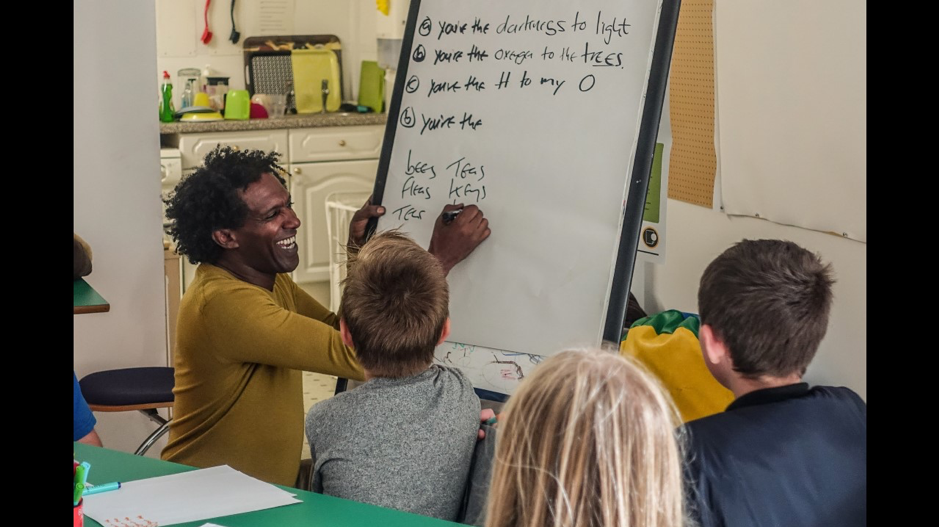

Lemn Sissay MBE, poet, author, broadcaster and self-proclaimed ‘child of the state’; and Charlotte Vincent, choreographer and director, were the lead artists, alongside other artists Becky Edmunds, Oscar Romp and Laura Bissonet. Adults in treatment services and their children were engaged in an exploration of substance misuse, parenting and attachment issues, which culminated in a performance at the Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts (ACCA), Brighton, in October 2018.

A Secure Base

One of Ainsworth’s principles was the idea that the caregiver provides a child with a ‘secure base from which to explore’, and this principle was present throughout the project. Working safely and without compromising the participants or the art, was at Art of Attachment’s heart. Attachment behaviours are activated in times of stress, danger, fear, excitement; working with the unknown during the project, involved taking risks for and with the participants, as well as the artists and for the organisation. Establishing a strong working alliance to build a ‘secure base’ was essential.

The project advisory group was multi-disciplinary and vital in it’s guiding role. My role was as clinical lead on the ground, observing, tracking, feeding back on the process and providing a holding function, alongside programme manager Alison Cotton who had the difficult task of straddling all aspects and making everything happen.

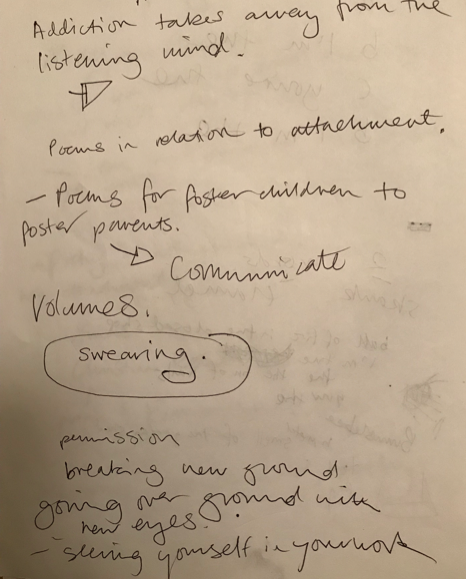

It is not a clean business at BOP, it involves working with trauma, chaos, pain and loss; it is neglecting, violating and violent. It is messy and it is not in the securely attached world. Therefore, the way the arts fit in with this has also been complicated and multi-dimensional.

Containment and Expression

Both lead artists’ approaches were very different, both successful. Lemn Sissay’s workshops were ninety minutes long, they were sharp and went deep. Charlotte Vincent’s nine months of workshops and research, involved a slow building of trust through time, culminating in a public performance. Over the course of the project, illustrations were commissioned by Oscar Romp and a film ‘So heartbroken, so long’ by Becky Edmunds.

‘Poetry is a place where the truth speaks’ Lemn Sissay

Lemn’s first workshop offered containment from the very beginning, providing a space that felt safe enough for the children, not just to sit, but to delve into their imaginations. It started on time and ended on time, keeping a tight boundary. The strip lighting was turned off and low lighting introduced. The room changed from ‘institution’ to ‘home’. Children were welcomed individually and by name.

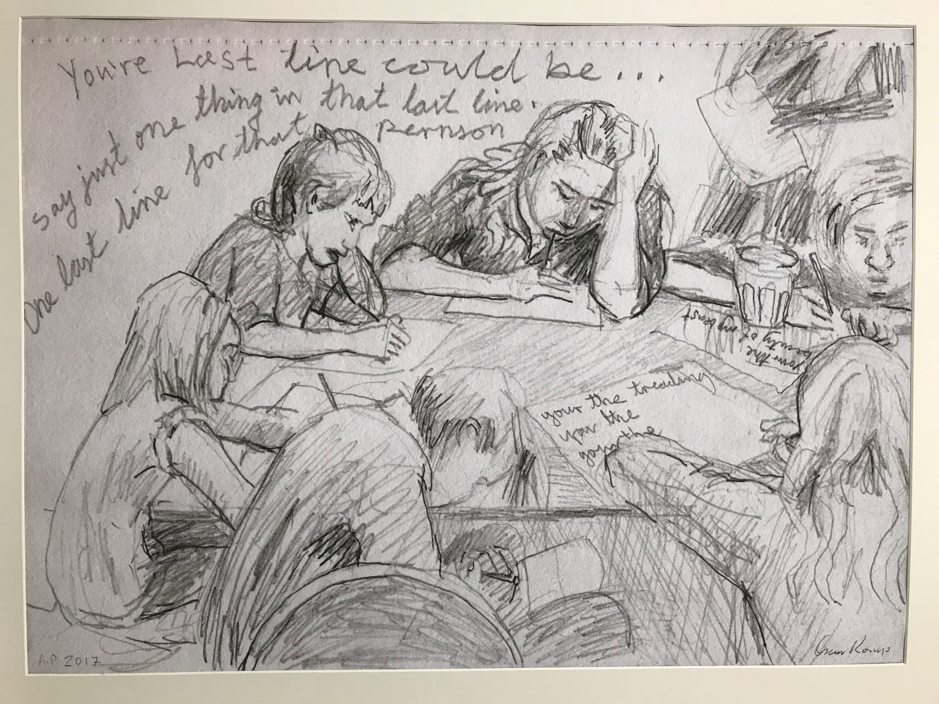

The workshop began with Lemn telling them, ‘I will be with you and not leave you for the next hour and a half ’. His presence demanded their full attention. The further a child drifted, the closer he kept them by his side. He invited the children to think of someone significant to them, without disclosing who this was. He encouraged them to think of an image and then to ‘go wild’ with the words, but within four lines, all beginning with, ‘You’re the…….’, which grew into four verses as the workshop progressed. I felt deeply moved as I watched some of the most dysregulated children I have worked with write with intensity, focus and in complete silence. There was an immediacy to the process and the children produced poems that were extraordinary, lines such as:

‘You’re the cold that makes me solid’

‘You’re the hot that makes me steam’

‘You’re the blustering breeze brushing through untamed hair’

Charlotte Vincent’s approach was polar opposite, her workshops required stamina, commitment and grit. I was present for check ins, check outs, crises, dramas, and struggled when it felt like the boundaries were being pushed in what felt like counter-therapeutic directions. The constructive tension at times felt appropriately dangerous, and demonstrated the fission between art and therapy in the task of containment that the project aimed to create.

‘‘The performance you see tonight is the result of many hours of talking, sharing, writing, recording, questioning, listening, moving, crying, retracting, redacting, translating, thinking, improvising, trying out, walking out and walking back in again in order to carry on”. Charlotte Vincent

This is a very accurate account of the process by Charlotte. Working intensively with a group of four women over nine months, produced the most powerful performance. This group experience invited people to share the raw material of their lives. Working alongside professional dancers and through Charlotte’s direction this material was translated into movement. Working with the body, movement and breath the group developed a strong bond, the workshops helped provide a rhythm and structure in the participants’ lives. One participant could not move for the first two months, refusing touch and keeping her coat on. By October, she was laughing and rolling on the floor in the group, on stage she was able to hold a three hundred-strong audience captivated as she performed.

On the night of the performance, starkly staged in the style of the Last Supper, the six performers were sat at a table, each with a microphone. There were few props – piles of paper, microphones, some wine bottles, and a baby doll.

With deliberation, poise, timing and breath, a lone voice spoke: ‘I want to talk about the difficult. It’s difficult. I am difficult. I was difficult, but words get in the way. Words like, birth, reject, birth, reject.‘

The looping, repeating voice samples, interrupt and overlap, stopping and then returning. Sound was a constant: heartbeats, breathing, testimonies and lullabies, a recurring theme.

There was visceral emotion where an infant one minute was enveloped in the sound of its mother singing, to interruption the next by sounds of violence and aggression. To be shunted rather than lulled, this brings us directly into the content of the Vincent Dance Theatre performance. It was beautifully executed, professionally performed, with shocking content; it was theatre based on truth, hard-hitting, indigestible truth.

The impact of performing this by the women themselves alongside the dancers to a sell out audience was transformative. In a thankyou card, these words were written by one of the women:

‘Thank you for giving me the opportunity to be part of Charlotte Vincent DRAMA, I have suffered mental health, drink and drugs for 33 years and The DRAMA has been the BEST therapy I ever had and I will be eternally grateful’

The Art of Attachment – a Dynamic Relational Model

BOP works with a ‘developmental’ model of attachment, understanding that relational patterns can be influenced by new experiences. The Art of Attachment was expansive in its ambition and approach. The participants were no longer reduced to a report, or a referral in need of a service, their experiences were relayed as deeply human, they were applauded with a standing ovation.

Everyone involved in the project came out changed. I am confident that there has been rich learning and I know that for myself it will take time to process fully. The project was a courageous experiment into the shadows of those who felt able to share. It showed that this messy process could deliver clean outcomes, through careful collaboration. Bodies moved, so too were emotions and the witnesses in the final show’s audience.

Art and Justice

People talk about giving people ‘a voice’, often referring to marginalised people. Lemn Sissay said that you can’t ‘give someone a voice’, when it is not yours to give – each of us has a voice of our own. Working alongside the artists has enabled not only the participants’ voices to be heard, but for them to be seen, in the spotlight – unapologetic.

Both the practice of art and of psychotherapy are concerned with truth, in this case the women and children of BOP were its subject. The Art of Attachment has allowed for the overlapping of many worlds and has facilitated deep listening. BOP is an innovative organisation that took a risk in doing this, which feels rare in our overly cautious world. As Al Alvarez in the quote above eloquently stated, ‘the authentic voice may not be the one that you want to hear’. This is exactly what the Art of Attachment achieved, it got people listening. A rare glimpse into the world of substance misuse and peoples lives was shared through art. This assures the power and necessity of art in society.