Screening Testimony: Law and Performance in the Age of the Videosphere

by Sean Mulcahy

Screening Testimony was a seminar and installation held at Monash University in August that sought to explore the effects of the use of screens on actors in court proceedings and how audiences respond and connect to the actor on screen.

The event opened with a talk by Dr Carolyn McKay of the University of Sydney Law School on some of the themes of the event drawing from her research into the technologies of justice, particularly the impact of video link technologies on prisoners. Carolyn is recognised for her empirical research into prisoners’ experiences of accessing justice from a custodial situation by audiovisual links. Her qualitative study based on one-to-one interviews provided evidence for her PhD thesis as well her recently published research monograph, The Pixelated Prisoner: Prison video links, court ‘appearance’ and the justice matrix. Carolyn’s creative practice encompasses digital video and audio, photo media and painting, and revolves around video and visual technologies in prisons and courts.

Last year, Carolyn participated in the University of Technology Sydney Designing Out Crime research centre’s audiovisual link project for the Department of Justice in New South Wales. The centre’s aims to bring design innovation to complex crime problems are part of an emerging global trend of designers and architects engaging with crime, justice and forensics. Another example may be Forensic Architecture, based at Goldsmiths, University of London.

However, it is fair to say that there is a general resistance to creative practice-led research in the law school, a methodology that is more typical in the visual or performing arts. For theatre and arts practitioners, innovative approaches are necessary to overcome this. Carolyn settled on not creating artwork through her PhD, but allowing her ongoing arts practice to respond to her research during her PhD. Thus, it was not so much practice-led research but practice-influenced research or, indeed, research-influenced practice.

Carolyn described her practice as “a habituation to materially thinking”, radically reconceptualising the software of justice and the technologies of audiovisual link as material objects, and focusing on their tactility or materialness. The hands interacting with a tablet computer, for example, are a material interaction joining hand, eye and mind together. Carolyn sees this kind of sensorial engagement as a way of creating new knowledge about the technologies of justice; moreover, a form of embodied experiential knowledge. This knowledge making also necessitates a reflexive practice, wherein the creative practitioner critically reflects on and analyses their work. Carolyn described the analytical and creative as different forms along a range of cognition. Embracing creative practice in legal studies may yield new understandings of justice.

The question of bodies together in space, and the mediation thereof, is a key question shared by both researchers in law and performance studies. Technologies of justice are challenging the notion of shared space, raw human voice and presence that were once typical to legal performance. Whilst performance studies scholar Philip Auslander has argued that “the legal arena may still be one of the few remaining cultural contexts in which live performance is still considered essential” (2008: 8-9), that thesis surely cannot hold today. Virtual appearance is now reshaping presence and the performance of justice.

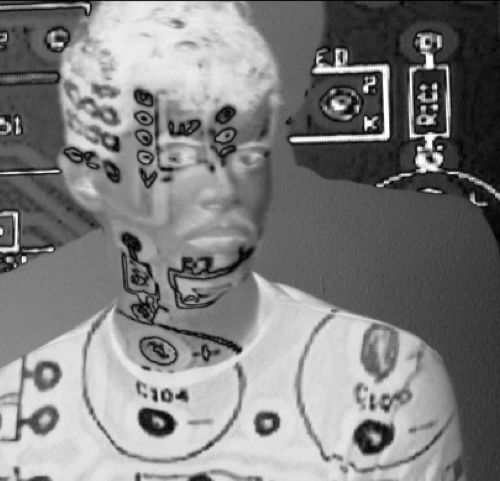

Carolyn’s incisive talk was followed by an installation that explored face-to-face and eye contact in digital testimony. Three screens were set up across a gallery-like space with an actor (myself) delivering testimony on a pre-recorded loop looking in three different directions: directly at camera, above camera and to the side. The camera then focused on three different angles – the testifier’s head and shoulders, hands and feet – which together, if connected, would make a full body. Participants were invited to interact with the screens – walk around them, touch them and smell them – and then asked how they experienced the testimony, how the testimony felt to them and how the testimony made them feel in an embodied sense. What emerged from this group discussion was stimulating insight into the acoustic, visual and other sensory dimensions of video-link and screens.

With the three screens dotted throughout space, participants’ gaze darted and flicked through the different images. There was a particular focus on the eyes of the testifier, which became potent and powerful signifiers of remembering. In communication, a participant will often read eye direction as an indication of whether a person is lying or recalling a memory. The face was also a powerful centre of meaning capable of deconstruction because of is expressive qualities. There was, however, less for the audience to interpret in the hands and feet. It was tempting for the audience to read the movement or gestures of the extremities as information about the sound. Perhaps this is less potent when the movement is complementary to the voice, but when it is different, it can raise questions about the authenticity of the words being said. When the screen was not focused on the face, the testimony was listened to in a different way. The sound was distinct from the image. This was not so in the screen with the speaking mouth. The interpretive potency of the face and, in particular, its eyes drew the audiences’ attention away from the words themselves and into a reading of the facial expression and eye direction. When presented with images of the hands and feet, the words were experienced more clearly and the audience was able to focus on their meaning more. Believability was important to the audience, who initially tended to evaluate the installation on the grounds of truth or authenticity.

The scale of the screens was also an important factor in the sensorial engagement with the testifier thereon. Whereas these screens were laptop-sized, life size screens might amplify the audience’s gaze. Performance practitioner and researcher Steve Dixon has experimented with scale of screens as a means of invoking presence in digital performance. Screens also flatten an image and, in so doing, other or dehumanize the actor on screen. The frame of the screen also enacts a form of digital incarceration of the actor. The body becomes “digitally encased and hermetically sealed on screen” (McKay cited in Mulcahy 2018: 135). In this installation, the hands came in and out of shot, which the audience found to be bothersome and rendered them imprecise for interpretation. The way that the frame thus cut off aspects of the body was especially potent.

Acoustically, the silences rang out most, giving weight to the answers of the testifiers. The face without sound spoke to the audience, its expression communicating a wealth of meaning. These silences would, in court, be filled with the questions to the testifier, which the audience was able to infer. Conversely, the looking was prompted by the noise of voices. The audience would oftentimes turn to look at a screen if a voice was coming from it. In an unexpected way, the noises coming from the screen worked to create an engaging soundscape of overlapping voices. Patterns were created acoustically and visually across the screens, inviting the audience to focus on the whole vista rather than focus in on one screen at a time. This was an experience that would be unusual in court, but a product of the mode of presentation in installation. Nonetheless, the overlapping of voices that one might hear in a bustling courtroom contributes to the soundscape and perhaps even musicality of justice. The vocal impact of mediation was also noticeable as against the unfiltered or raw human voice. Most of the legal scholarship on recorded voice tends to focus on its admissibility in cases where it is surreptitiously recorded, but this performance-led research raises different questions regarding the acoustic quality of recorded voice and how that differs to live voice.

Participants stated that they would not have touched the screens if not invited to do so. This very much depended on the device. As the testimony was screened on laptops, the desire to touch was not strong; this may have changed were it screened on a hand-held smartphone or, conversely, if on a mega screen that endeared a more embodied response in the audience. The size of screens could this affect the tactility of testimony. When touched, the monitor felt like how the audience expected it should. There was no feeling of overheating or the slight tingling sensation one might get from the static electricity when a laptop is not plugged in correctly. Thinking through legal performance tactilely is challenging given the prominence placed on the acoustic and visual senses. Whilst prohibitions on noise in the court are explicit through signage and the gavel, prohibitions on touching are more tacit. The architectural arrangement of space prevents most from touching the screens or, indeed, any live testifier. However, there is a haptic possibility in live performance; that is, the possibility of touch between actor and audience that even if unfulfilled lends a powerful potency to the performance. There is no such possibility in digital performance, thus creating a degree of distance between the performer and audience. The shared proximity in space between actor and audience is absent in a digital – as opposed to a live – performance of testimony. The state of the performer both spatially and sensorially dislocated from their audience has flow on implications to the other senses, such as smell and taste.

One can gather from this group discussion that physical presence and proximity is experienced differently when testimony is mediated through screens, but further research is needed to conclude how (the possibility of) touch and contact is experienced in live versus digital performance. It would be interesting to explore how testimony feels in a tactile sense. Further research may also explore how the othered senses, such as smell and taste, are experienced in legal performance, live or digital. What this seminar and installation did explore in depth was presence, connection and the acoustic, visual and haptic senses in digital testimony and, through this exploration, generated interesting reflections on what an audience looks, listens and even feels for when bearing witness.

Carolyn McKay’s The Pixelated Prisoner: Prison video links, court ‘appearance’ and the justice matrix is available for purchase from Routledge