Migrants in Art / Migrant Artists Rights

While many may have a “vision of culture without borders”, the reality of the hostile environment is heavily felt within the UK cultural sector for workers with migrant backgrounds. As legislative networks encroach and try to limit the possibilities of those caught in them, the role of art becomes even more important as a tool to educate and communicate. However the inequalities faced by migrants as artists are also found within the art world and its creations. Very often migrants are depicted as subjects rather than makers. ‘Refugee art’ brings up many questions of consent, the often vulnerable status of what migration means, with racial, legal and socio-political connotations attached.

Whether art produced by migrants or art made by non-migrants about migrants, they end up limited by their identity in ways that other artists may not.

Drawing together themes of creativity, law and exile, the Migrants in Art / Migrant Artists Rights seminar sessions will interrogate theses ideas through three events on 21 July, 18 August and 15 September.

Migrant in Art // Valuing Art // Migrant Artists’ Rights

1 – Migrant in Art 21 July 2021

This first session opened the conversation in a broad and conceptual sense, asking questions of the cultural sector, the content of art works, who speaks and who gets heard. Laying the landscape of ‘exile’, including a theoretical and historical introduction of the meaning of home within the concept of HOMEing.

A story of ‘artists before lawyers’ is not more clearly told than by ‘The Hummingbird Project’ who instigated the arrival of further international organisations to allow for a formal presence at the camp with their presence at the Jungle back in 2015; the art therapists paving the way for human rights NGOs and beyond. Further, video art by Detained Voices visualised the experiences of people exiled in detention prisons as they await a forced departure from the place they call home.

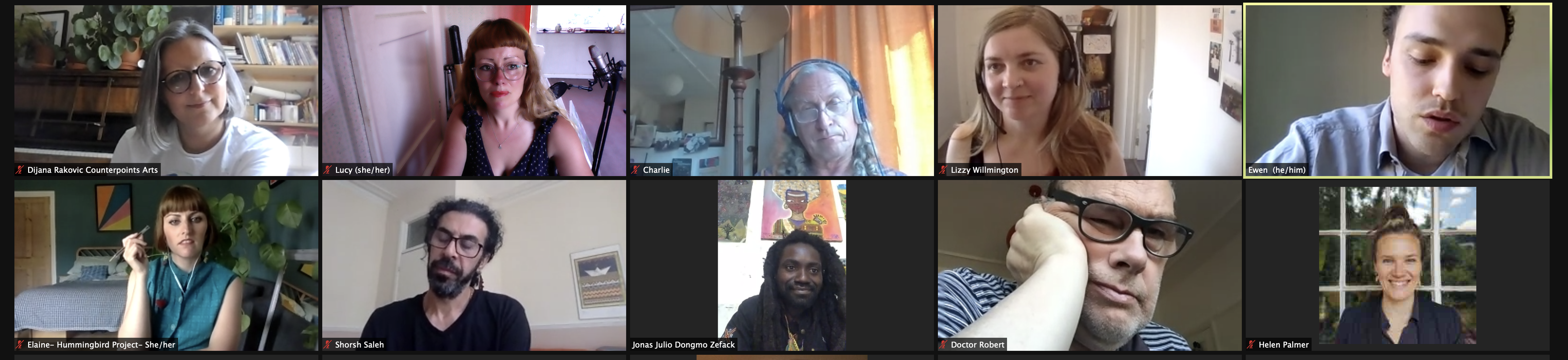

We invited Hummingbird Project, Detained Voices, artists Boyesenfin, Shorsh Shaleh and Counterpoints Arts to discuss the role of the migrant in art, migration and art, healing before and through the law, law as creating the exile, the role of art as advocacy and arriving before the law.

To listen to a recording of the event, please click here.

2 – Value of Art: Artist Showcase 18 August 2021

Please find tickets here.

With artists Akila Richards and Helen Knowles showing their work relating to migrant artists’ labour rights.

3 – Migrant Artists’ Rights: Policy and Practice 15 September 2021

Please find tickets here.

Working with migrant cultural groups and unions this will be an interactive and productive session which will bring together themes and conversations from the previous two sessions to work towards a practical/creative outcome.

Confirmed are representatives of Artists Union England, Migrants in Culture, amongst other participants.

We welcome submissions from artists, activists, lawyers and writers to contribute to this last panel. We particularly encourage submissions from artists, writers and researchers from migrant backgrounds.

Please send abstracts of up to 250 words for submissions text and non-text based, including images, video and sound files, with a brief biography of 100 words to willmingtones@cardiff.ac.uk, l.finchett-maddock@sussex.ac.uk and charlieblake_uk@yahoo.com. The deadline for sending information is 31 August 2021.

****

2020 was a year where the precarious underbelly of our economic and political systems were upturned, as attempts are made across the board to avert the impact of Covid-19. It was the year where culture disappeared, where it was uploaded online; its sector workers put on standby as the world avoided an inevitable death swerve – or told to retrain and get other jobs. And 2021 is not too much different.

The fragility of the cultural sector comes to the fore, its economic viability in tatters. What does that say for art itself, and the way that law sees art, purely as a concept, or something ‘nice’; as assets to be bought and sold; the ‘dark matter’ of cultural work slipping through the net of any support packages. This was on top of an already highly precarious and unequal industry where the humble work of thousands often supports just a handful of the most famous. Its historically white heteronormative, ableist structures compound the difficulties faced by black cultural workers, those of colour, and of migrant status.

A recent survey conducted by Migrants in Culture, a “network of migrants organising to create the conditions of safety, agency and solidarity in the culture sector for migrants, people of colour and all others impacted by the UK’s immigration regime” who are guided by a “vision of culture without borders”, reports on the barriers faced by migrant cultural workers in the UK. Their recent survey in 2019 collected key information on the experiences of over 600 cultural workers, migrant and non-migrant. It found that 90% of cultural workers feel angry or fearful about their treatment as a result of the ‘Hostile Environment’, whilst a majority of cultural workers experienced racial profiling or discrimination (60%) as a result of the policy. During the pandemic many cultural workers will have no recourse to public funds (NRPF) and therefore access to the furlough schemes or universal credit. The Hostile Environment does what it says on the tin: its primary objective is to make living in the UK as difficult as possible for migrants, so that they may ‘voluntarily leave’.

The inequalities faced by migrants as artists are also found within the content of art work.

Very often migrants are depicted as subjects rather than makers, no more presciently than in the bringing of the wrecked shipwreck where upto 1,100 people perished, as a piece of art to the Venice Biennale in 2018 by Swiss-Icelandic artist Christoph Büchel. ‘Refugee art’ brings up many questions of consent, the often vulnerable status of what migration means, with racial, legal and socio-political connotations attached. Whether art produced by migrants or art made by non-migrants about migrants, they end up limited by their identity in ways that other artists may not.

Similarly, in a year where we have witnessed the pandemic spread across countries and its peoples all around the world, you might think that the migration flows around the world have all but stopped as well. Where all but one issue criss-crosses our screens and minds on a continuous loop, underneath this veneer of virus-related news, the movement and flow of peoples continue on despite the aversion of the media’s gaze.

We have repeatedly seen continued English Channel crossings that have been made by those desperately fleeing collapse and persecution throughout 2020. By 20 October, the total number of crossings in 2020 reached 7,294. On 29 October, a Kurdish family of five died trying to cross the channel, their boat sinking off the coast of Dunkirk – the father, Rasoul Iran-Nejad, 35, mother, Shiva Mohammad Panahi, 35, and their three children all below the age of nine. Not just one but two generations disappeared into the swollen tumult of the waters that day. And yet, if they had made it to the shores of Dover who knows how the law may have come to them. An agreement between the French and the UK under the Sangatte Protocol 1991 and the Touquet Treaty 2003 has effectively swapped the topographical seaboard of the two opposite countries, meaning French border guards can check migrants entering France, at Dover, and the same vice versa for UK Border Agency officials to be able to ascertain a migrants’ status before entering UK soil. The sovereign territories of each state overlap in a complex orchestration of refusal. This is why there remain encampments at Calais, even though the infamous and yet to some extent more formalised camp of the ‘Jungle’ was evicted by French police in 2016. This legislative network of mechanisms to make access to the UK as difficult as possible is then continued once arrived, most notoriously through the implementation of the ‘Hostile Environment’ policy first announced in 2012.

These depictions of law’s edge are dark, desperate, and have only accelerated during these times as the uncertainty of the climate becomes more real and populations are moving, no matter what; come what may.

If culture is not economically viable, then what can it do on the border encampments that exist along the many terrains across the world? A story of ‘artists before lawyers’ is not more clearly told than by art therapy group The Hummingbird Project who thanks to their presence at the Jungle back in 2015, instigated the arrival of further international organisations to allow for a formal presence at the camp; the art therapists paving the way for human rights NGOs and beyond.

For more information of this project please contact l.finchett-maddock@sussex.ac.uk.