Layers of Creativity: An Interview with Graham Rawle

by Oğulcan Ekiz

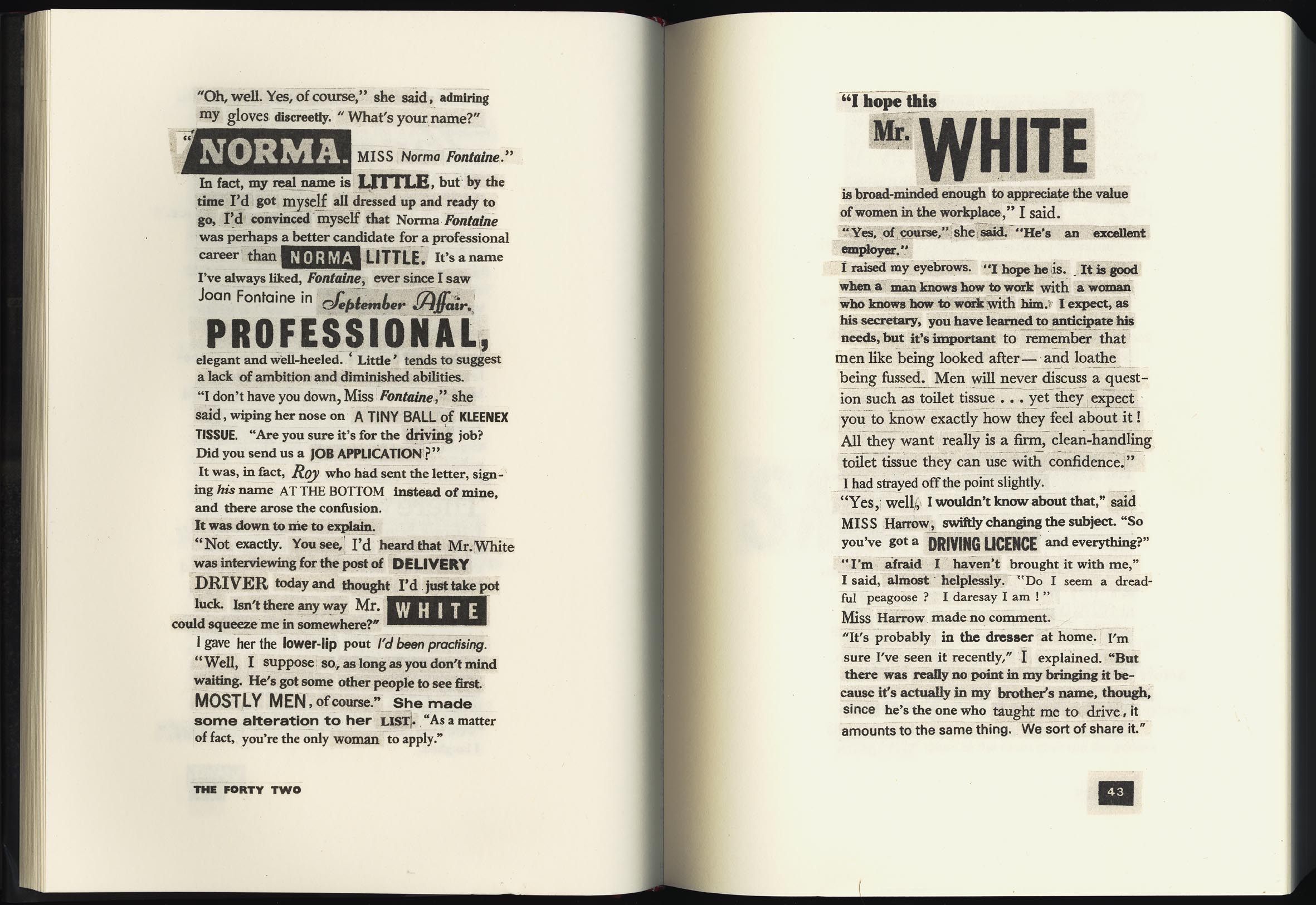

Copying in the process of creativity has long been a controversial topic in the copyright discourse. While Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 provides exceptions for certain dealings, the concept of originality remains to be one of the key concepts of the Act, thus uncertainties arise for the ones who rely on copyright-protected works in their creative expressions. Graham Rawle, a UK-based writer, artist, and designer, frequently utilizes third-party materials in his interdisciplinary art practice. In Lost Consonants, a weekly series of collages that have been featured in the Weekend Guardian for 15 years (1990-2005), Rawle illustrated comical scenes shaped around sentences from which one vital letter has been removed, such as – ‘The Judge accepted the defendant’s pea bargain’. His reinterpretation of The Wizard of Oz, whichillustrates over 100 images of the visual world Rawle created via the techniques of collage, photography, and model-making, won Book of The Year 2009, and Best Trade Illustrated Book Award at the British Book Design and Production Awards. In this interview, we focused on two of his projects in order to interrogate the relationship between copying and creativity: Woman’s World (2005), a 437-page collaged novel created entirely from found texts snipped from vintage women’s magazines. The novel is about Norma’s struggle to live up to the prescribed ideas of feminine perfection. And the subsequent Woman’s WorldFilm project where Rawle aims to use a similar methodology, working with film clips to narrate Norma’s story.

How do you define your relationship with the source material you use?

The collage process is about making the best from what is available. Limited choice can be incredibly enabling because it forces you to find more inventive and imaginative solutions. One interesting thing that happens is that the found material retains a suggestion of its original context: the flavour, syntax, message, style, purpose. All of this can be carried through into the new assembled work with varying degrees of visibility according to the aims of the piece. This was particularly relevant to Woman’s Worldwhere it was important for the distinctive voice and moral tone of the women’s magazines to come through in Norma’s narration.

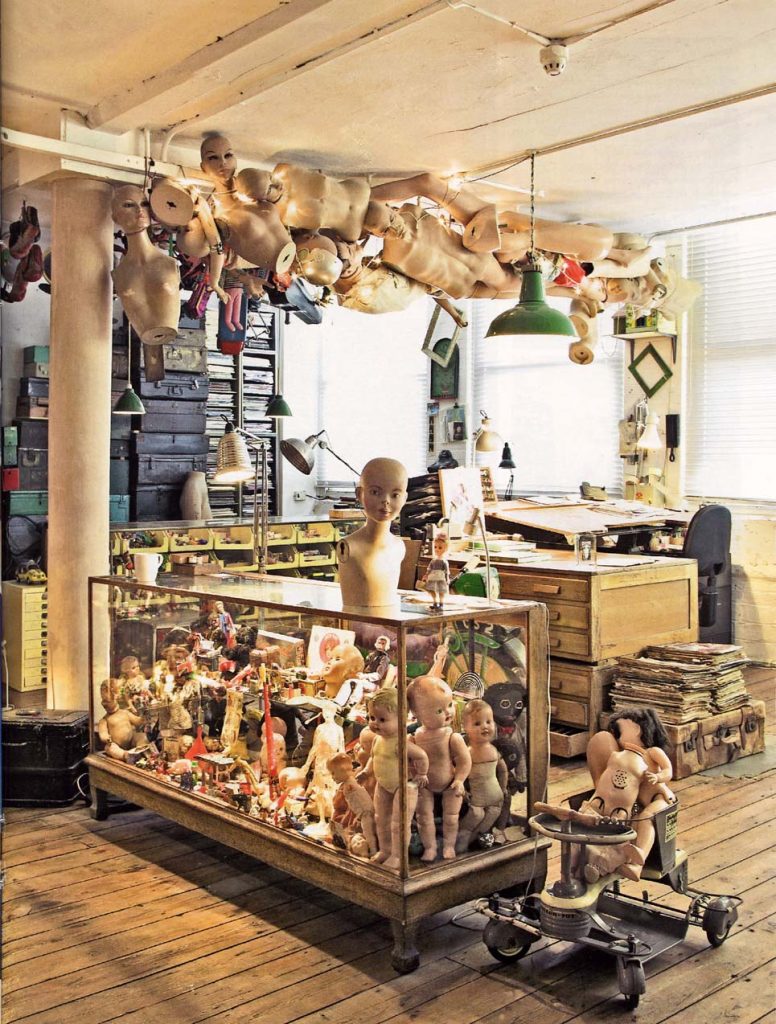

How did you start collecting the magazines and toys from the 50s and 60s? And when did they become a source of inspiration for you rather than a collection from a particular period?

I’ve always collected, and there has never really been any distinction between what is for work and what is for my personal collection. Nearly all of my projects are set in the 1950s and ‘60s and use material from that period. The things that I collect are often deeply connected to my childhood and are loaded with personal associations. They provide the appropriate context to tell my stories. Anything can get used if the work demands it.

Woman’s Worldfeatures around 40,000 fragments cut from over 1000 copies of women’s magazines from the 60s. I assume that you did not seek permission for the uses. It would be quite discouraging considering the volume of the material you used. Although artists are more inclined to not seek permission for such uses, many other professionals in the visual arts community do. What do you think about this so-called ‘permissions culture’?

I’ve worked as a collage artist for over 30 years, using copyright protected material without seeking permission and, like many collage artists, have learnt through experience what I’m likely to ‘get away with’ rather than really knowing anything about copyright law.

The original source of most of the material in Woman’s Worldwould be difficult to trace, but sometimes a recognisable line is taken from an advert to show how, through familiarity, a glib advertising slogan has become part of Norma’s vocabulary. These fragments and their sources, being more conspicuous, become potentially more litigious, but these lines are an essential part of the text. I didn’t seek permission because I believed that the pieces were a small enough part of the greater whole I was creating. I now know that legally, this is a shaky defence to adopt, but in truth I also thought it unlikely that anyone would contest any of the uses so I was prepared to take the risk.

If I had sought permission to use copyright protected material, 90% of the work I have produced over the years could not have been made, and certainly Woman’s Worldwould never have been published. That said, I like to think I use found material responsibly. All the choices I make are subject to a personal critical judgement to evaluate what I think is ethically or morally appropriate to use, even if it may not be strictly legal.

In Woman’s World, you used words from various types of texts, from short romance stories to advertisements. Phrases that were coined to advertise beauty products became Norma’s expression in the novel. In this sense, you transform the third-party material into something new. What do you think about the notion of transformative use?

The law is hazy on this as it’s difficult to make hard and fast rules about what should or should not be permitted, but there is some provision for the avoidance of clearance rights under the ‘fair dealing’ exception for transformative works. Artists are often unsure about their rights and can be wary of using copyrighted material. Many collagists feel the need (often unnecessarily) to moderate their use of found material, potentially weakening or diluting their idea. I know a little more now about copyright and fair dealing than I did when I created the book. Back then, I knew next to nothing, but I felt intuitively that what I was doing would be understood, both legally and morally, as a creative endeavour that relied on the collaging of found material for it to succeed. The reader should be able to recognise, or at least understand, where the source material has come from and how its core values define Norma’s fabricated persona, informing her opinions and shaping her syntax. Only by using the original material could this hold any veracity.

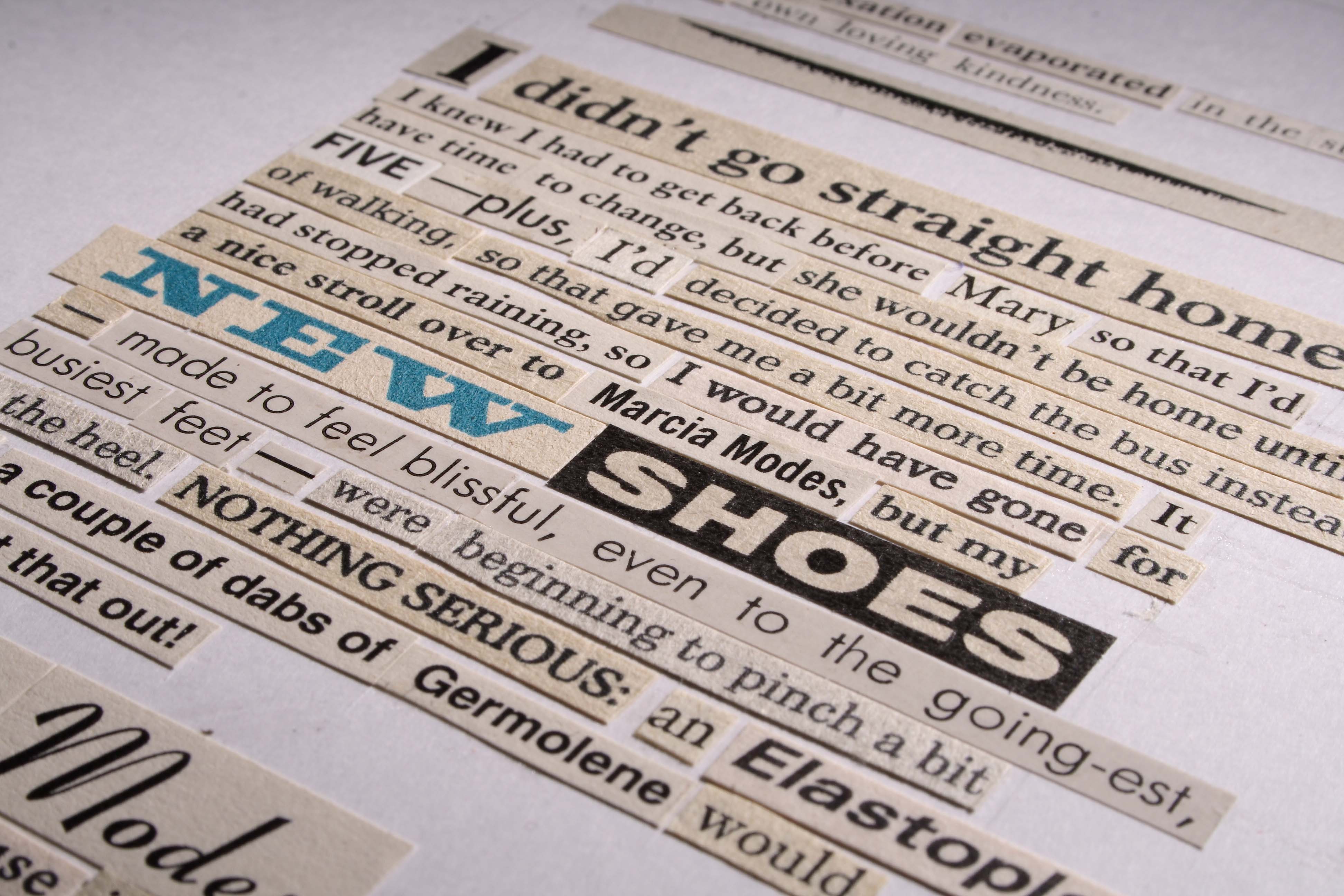

There are various lengths of cropped texts in Woman’s World. Some of them are just letters, some are words and in some pages we see a whole paragraph cropped. I believe the latter was more challenging to reconceptualize. From the copyright perspective, contrarily, the less you copy the more likely your act would be found non-infringing. Is it possible to be self-conscious about how much you copy during the process of creating the work?

Well, when I was immersed in it, my main objective was to tell the story as effectively as possible. I recognised that it was important to keep an eye to moderate my usage, but it was more of a stylistic or moral consideration than a legal one. It was sometimes appropriate to let Norma’s narrative description of a scene run away with itself with a lengthier chunk of appropriated text. But most of the time a sentence would be composed from several fragments sourced from different magazine pages. My best writing came about as a result of the invention that the methodology demanded, generating unexpected similes and metaphors in sentences that I would otherwise have been unlikely to come up with: ‘Red rage rose within me like the mercury in a toffee thermometer and I knew I had to leave before I reached the boiling point for fudge’ – or ‘Her stare was as cold and as still as a dead man’s bath water.’

You are now working on a new project, Woman’s World Film. Instead of the found text, you are working with found footage. Can you compare working with text as raw material versus working with the footage?

The methodology is almost identical. Film clips are sourced, sorted and stored in a temporary archive. From them, an approximation of the Woman’s World story is assembled, piece by piece. The difficulties of editing together a coherent and engaging story from thousands of mismatched shots are manifest. The book was a hugely complicated process and took five years to produce; the film, I now realise, is ten times more difficult.

In the book, when I needed a character to say ‘hello’, any hellocut from a magazine would serve the purpose. The word’s original inflection, whatever it may have been – cheerful, dismissive, suspicious – was removed and a new inflection assigned through the new context. The sense of the word helloin ‘Hello, stranger’is very different from the one in ‘Hello, what’s been going on here?’In the book these two hellos would be interchangeable, but in the film the inherent intonation and cadence remains, so I have to find the right one otherwise it won’t make sense. These limitations force me to question why I’m looking for helloand notgreetings or how do you do, or whether the character needs to speak at all; maybe a nod will be better. If Norma breaks a heel on her shoe as she walks down the street, rather than spend months looking for the shot I want – close-up of heel breaking on early 1960s lady’s shoe – I have to reconsider the intention of the scene. If the broken heel is to suggest her confidence being undermined, there may be alternative ways to show it: a dog snarling at her or a tree branch knocking off her hat. As a designer, I believe this is a healthy way to think because I’m stating the problem rather than a preconceived solution.

Have you ever had any copyright-related problems, whether in your artistic or academical works?

Rarely. A long time ago I was told off by the Red Cross for using a red cross in a picture; they told me that the red cross was a copyrighted symbol of the American Red Cross and that through my flagrant misuse of it, lives may be at risk. The absurdity of the accusation was made even more daft by the fact that my red cross was an x rather than a +. You can’t have it both ways. There have been one or two other minor copyright issues, but nothing contentious.

I think the reason I haven’t run into any problems is that I understand the nature of what I’m doing and I’m pretty good at disguising any source material that might present a risk. Sometimes though, as will be the case with the film, the content and sources are very visible, which is why I’m now looking into the copyright implications more rigorously. I am working with Charlotte Waelde, Professor of IP Law, on a proposed AHRC Network of interdisciplinary experts – lawyers, academics, artists and film industry professionals – who will focus on the copyright issues surrounding the making of the Woman’s Worldfilm. The group aims to explore pastiche in filmmaking and its ‘fair dealing’ potential within shifting copyright law and to understand the justification criteria for artists using copyrighted material that carries cultural, historical and contextual references considered essential to the transformative work.

What do you think about memes? In memes, we see people transform the context of a visual work. And it is quite widespread. Do you think people become more engaged with cultural products in creative manners in the digital era? Or are we just seeing more examples since they are now more accessible thanks to the Internet?

Anything that diminishes individual creative thought is bad and anything that inspires it is good. Memes have generated some interesting stuff, but the danger is that these trends can foster formulaic responses that pale in comparison to the original idea to subvert or parody something. The Keep Calm and Carry On WW2 propaganda poster is a good example. There have been hundreds of tiresome renditions – pastiches of pastiches. Most don’t bother to question, and thereby understand, where a thing came from and what it was originally used for. When you’re repurposing found material I think it’s important to do this. The other day I saw one: Keep Calm And Love Penguins. I mean, really?

Do you have any unrealized projects?

Well, yes, the film, obviously. I have other projects on the back burner – I have another novel planned and I’m looking at ways to turn my book Overland into a film and theatre piece – but at the moment, the film is demanding all my attention. It’s the ideal project for me because it allows me to explore all of the things that interest me: collage; sequential design; narrative structure, film montage and continuity. I’m fascinated by what can be made to happen in the gap between two images, two pieces of text or two film clips and the role the audience plays in creating the story.

My early career was in music and this project presents, for the first time, the opportunity to include this in my work. The use of diegetic sound and music will play a critical role in smoothing over jarring visual joins between mismatched shots. The music, composed from existing film scores and incidental music is collaged, layered and blended to create new music tailored specifically to the assembled visuals, helping to reinforce or redefine the dramatic mood.

Though it’s a painstakingly labour intensive project, I enjoy the engrossing detail: studying the timing of the blink of an eye and what that can convey, or playing with audio to blend two unrelated words in a line of dialogue. But I also enjoy studying the overall narrative shape and balance of a story and how that plays out cinematically. It’s a project in which I learn to understand film editing styles techniques from that period by watching hundreds of British films from the 1950s and 60s. It’s taken me over 30 years to get to it, but I think I have devised the dream project for myself; it has everything I want.

Find more of Graham Rawle’s work at http://www.grahamrawle.com/