Interview by Oğulcan Ekiz

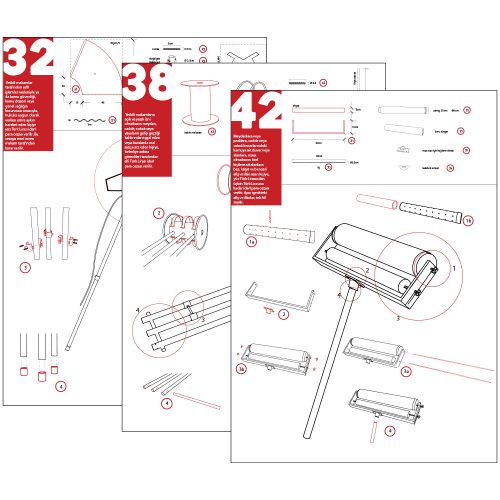

Are we all passive observers in public space? If so, how do we become active participants of the city we live in? Co-existing in public space is always a controversial topic in Turkey. Fundamental to co-existence is our intercommunication. In ’32, 38, 42′, Istanbul-based designer Başak Tuna questions methods of communication in public space and the boundaries set by the Turkish Misdemeanour Law. The installation targets three specific articles in the code, Articles 32, 38, and 42, which respectively state the following acts are misdemeanours: Disobedience of an order, Occupation of a public space, Putting up unauthorised banners. Tuna argues, however, that the said acts are methods of communication and introduces to the audience three objects that they can use to reclaim their engagement with the cities. The following is an excerpt from our conversation.

When I was doing some research for the interview, I revisited my old law books to refresh my memory on Turkish Misdemeanour Law. I wish someone had warned me in advance that what I was looking for did not actually exist, before I had lost a good hour. The reason is that 32, 38, 42 creates a fundamental distinction between the legal code and the art work itself. While the code defines the stated acts as ‘misdemeanours’, they are mediums of communication from your perspective. How did you realise there is a difference between your perspective of the code, and the code itself?

The starting point of 32, 38, 42 was the relationship I have with society and how much of a personal space I have in it. We all try to claim a personal space when we are in public, often without realizing that we do. You put your earphones here on the table, hence you claim this area. As such, when you bump into someone as you walk on the street, you feel interrupted. I came across the Misdemeanour Law when I was researching these kinds of interactions we have in public space. Its name took my attention. How do we label something as ‘misdemeanour’?

So you didn’t specifically look for a legal issue to work on?

No. It is actually my senior design project that I did as a part of my industrial design education. It has little to do with the field itself but I was lucky because my supervisor, Can Altay, encouraged me to work on it. The project came from my personal experience from walking on the street. I guess this may be the result of how being a designer affects your way of thinking. Say, you sit on a sofa that gives you a backache. You fix it with putting a toss pillow behind your back. Then you see other people having the same problem. This was something like that. On the other hand, the work has a lot to do with living in Istanbul. Everything is so intense here, on the street.

Yes, sometimes it feels like a survival game.

Yes, like a boss battle.

How did Istanbul effect the work?

I walk through Taksim every day to the place where I work. Every day I see police barricades spread around the neighbourhood. The barricades not only limit your area of movement but also provide a space for the police. They have coffee and tea inside and spend the whole day there. If you do something similar, it is ‘occupying the public space’, hence, it is a misdemeanour. This arbitrariness is what made me angry.

The idea started to shape around the time of the Gezi Movement. The public authority there conducted some acts that would be misdemeanours if we had committed them. In the repetition of those acts, you observe their sense of superiority over us.

The articles you target have a strong link with Gezi. The unauthorized banner especially. Because in Gezi, we observed that people were communicating with banners, graffitis and street writings. The public space was an active part of our intercommunication, whereas today we are surrounded by the plurality of mages in public space that worksmore like a monologue. We are continuously exposed to advertisements on billboards, bus stops, and buses. The Banner is a way to communicate a message, unlike the advertisements on billboards. What would it be like if all the spaces that are reserved for advertisements were used for individuals’ intercommunications?

Maybe something like Twitter. Imagine if we have spaces where everyone can post things. Maybe not everywhere, but in certain areas of neighbourhoods. Like bulletin boards you see in Starbucks. It would be quite fun to engage in that kind of interaction with people. It could gamify our daily communication, and in return, we may establish stronger connections with other people.

It may make being out on the street something fun. We definitely need it because we are often on the street in order to go somewhere else. This is especially true for Istanbul. And there is always this rush and panic. But this is not particularly true for you. I noticed that you often use your Instagram page to display what you have encountered with on the streets. As you put it, the images you share reveal the ‘randomness of daily life’ in Istanbul.

Yes, I am somehow conditioned to do that. I constantly observe the relationship between people and objects. I guess this comes from my industrial design background. This morning, I saw this applique alongside with a clock that had a golden hour and minute hand. In the middle of these two objects was a surveillance camera. This was on the wall of a parking lot. The former two have a strong connection with the concept of ‘home’. But when I saw those objects next to a surveillance camera, they reminded me more about the family pressure. So, I let my thoughts flow with these random assemblies of objects.

Have you ever lived outside Istanbul?

I grew in a village in Bursa. The freedom in the village is utterly different. The only thing that reminds you about the time is the call to prayer. That is how I knew it was time to go back home. From that freedom, coming to Istanbul was totally different as a teenager. First of all, you start living in a building. There are different dynamics in your daily interactions with your neighbours from downstairs and upstairs, and the shopkeepers in front of your building. I was also a bit of a rebel. I rejected using the school bus and went to school by myself. I always tried different ways to go back home. When you move from somewhere really small to somewhere enormous like Istanbul, you find yourself questioning things that are quite daily for others. It was weird for me that I was constantly in the same place with all those other people, and yet there was nothing connecting us. For example, if you travel with the ferry daily, there are the same 15-20 people that you see every day. Yet you have no idea who those people are. In the village, you know everyone who you share the same place with.

What do you lose when you move out of that environment where everyone is familiar to one another?

For example, it does not matter where you sit in the village. You can sit on a stone, on the log in front of the house, or on a broken chair. It does not matter. But here people find it strange if you sit on the floor on the street. Or, what you wear and the objects you carry with you become so important. Here, we define one another through these things. I guess my sensitivity towards the objects comes from this.

There are too many eyes that are ready to judge you. I guess this creates a self-consciousness in an unhealthy way.

Yes. And we all do that. And we are all affected by it.

In an earlier interview you said that you were not totally satisfied with displaying the work in an indoor exhibition area that – as a result of being an indoor exhibition space – limits people’s access to the work. Do you want to further comment on this?

Yes, I said that it might have been better to display the work on the street. On the other hand, the work might not have truly reached as many people as if it was on the street. Because it would not be noticed. When you put it in an exhibition area, it becomes something to be looked at. When the same object is on the street, however, it becomes something without an identity. People don’t really notice what surrounds them when they are on the street.

But I still think it should have a physical connection with the public space. Maybe I should have put the banners on the street. They are the central part of 32, 38, 42. It is how the work communicates with people since it shows how people can make those objects. Some people could even improve the objects. They may come up with better solutions.

Yes, the banners are quite interesting. As someone who deals with copyright daily, I was very alerted about this idea of inviting people to copy your work. You sort of say ‘take it, and come up with something better.’ It is somehow akin to the open source culture that often arisesin the digital world. How does it work for physical objects?

I used materials that are easy to obtain to make the objects in 32, 38, 42. I used broomsticks, which look cool but you can buy them for 3 Turkish Liras. So the objects are both easy to find and cheap to remake. And people are getting used to putting materials together, thanks to online platforms like Pinterest, and IKEA-like products. I wanted the objects to be reproduced easily since they are a call for people to reclaim their own spaces through these communication methods. Therefore, the banners are the central element of this work.

Do you have any unrealised projects?

I find the concept of temporariness quite interesting. Everything on the street is temporary. They will eventually be covered with another layer. Like the graffiti. You make a graffiti on a wall on the street and it will be covered by another graffiti or painted over. I have been thinking to do a photography exhibition that works like that. I would choose a spot and hang a photo there, leave it there for a while and pin another one on top of the first one. In the meantime, I would observe how the local people or a passerby would interact with the images.

Do you plan to work on a legal topic again in the future?

Yes, I am planning to make a fake legal code. I plan to write articles that are either humorous or too ruthless to be true. I plan to leave them behind in places like coffee shops as if I had forgotten them. The key part is the reaction of the person who finds it. Will she just leave it there, or maybe share it on Twitter saying ‘I just read this and…’?

Did you receive any feedback on 32, 38, 42 from people with a legal background?

No, I did not. I would like to hear what you think.

I like it. I like everything that moves law into a visual setting.